“He created a large zone of ambiguity.”

That’s what the Catholic writer Ross Douthat said recently to summarize the worldly contributions of the late Pope Francis. A genius summary of the man, I thought.

Over the years I thought the Pope could do more. Should have done more. Probably he couldn’t.

But really. God didn’t want women to think too much or wear cardinal’s hats? Just do all the hard work and bear the thinkers?

But I love Douthat’s idea that one of the late pope’s big contributions was creating “a large zone of ambiguity.”

What could be a bigger contribution to the world right now, or maybe ever?

Humans are surprisingly and intensely evolved in the direction of non-ambiguity, it seems, and not to the good.

I am right and you are wrong.

I am good and you are bad.

I am smart and you are dumb.

I am loved by God but you are not.

If there’s anything the world needs badly right now it’s humans who can be comfortable with ambiguity.

Allowing ambiguity into our thoughts and conversations takes time. It also takes careful study. Surely one of the great achievements of a higher education is the enhanced ability to entertain ambiguous ideas, to be comfortable knowing you may not know.

Attempting to put down thoughts in a memoir, trying to understand events and situations as “stages en route to decisive self-recognition,” as Sven Birkerts describes the process in his book, The Art of Time in Memoir, brings one soundly, if not immediately, to a place of ambiguity, I discovered.

When writing his own memoir, Birkerts says he found himself asking: What did my so-called real memories add up to? What were they telling me that was different from the authorized version I had of my life?

Are popes allowed to have such thoughts? To venture beyond the “authorized”? That seems to be what Douthat was talking about when he described the “large zone of ambiguity” the late pope created. A zone where not all questions had answers. A zone where the rules were suspended temporarily for further consideration. A zone where new ideas were allowed to take shape, even if only theoretically. A zone where even clear memories were sometimes maybe suspect.

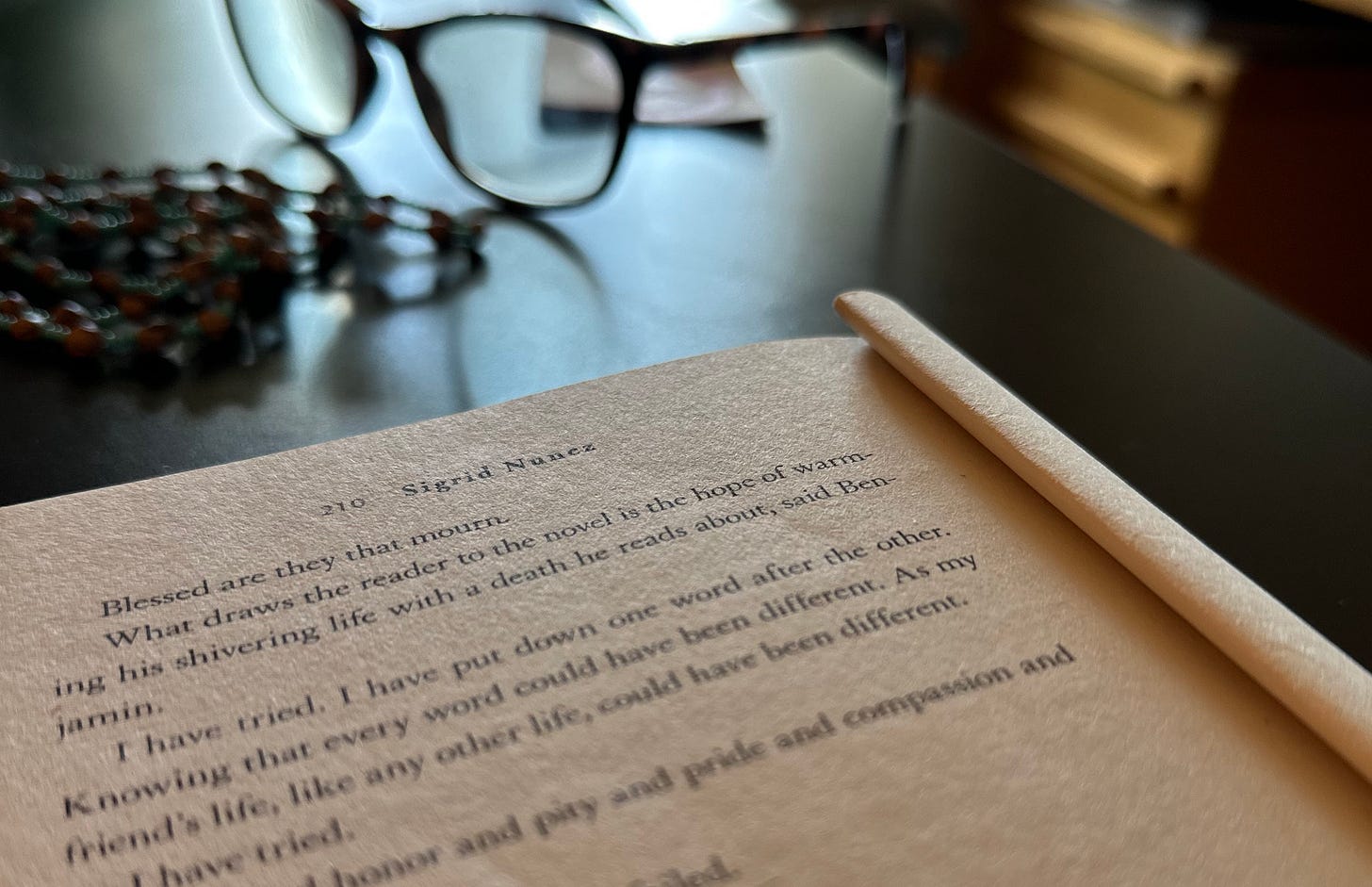

Among the last sentences in Sigrid Nunez’s novel, What Are You Going Through, are these:

“I have put down one word after the other. Knowing that every word could have been different. As my friend’s life, like any other life, could have been different.”

There is no question mark at the end of her book title, even though it is a question.

That might be called a touch of ambiguity. The word “different” hints at profound ambiguity.

Women, in general, are much better at ambiguity than men are, I imagine. (In order to stay ambiguous I am writing “I imagine” rather than “I know” or “I am certain.” Let’s just let it hang there — “I imagine.”) For another time.

So we give Pope Francis points for creating ambiguity while living in a culture of sparse ambiguity — and to Ross Douthat for describing it as an achievement.

I don't often agree with Ross -- on much of anything, actually, but I appreciate the way he thinks and how well he articulates his thoughts. This I do agree with. Excellent, Ross -- for all of us. Thank you, Jane.

Candis

Jane,

This is so insightful. If only more of us could live in the world of "grey".

Libby