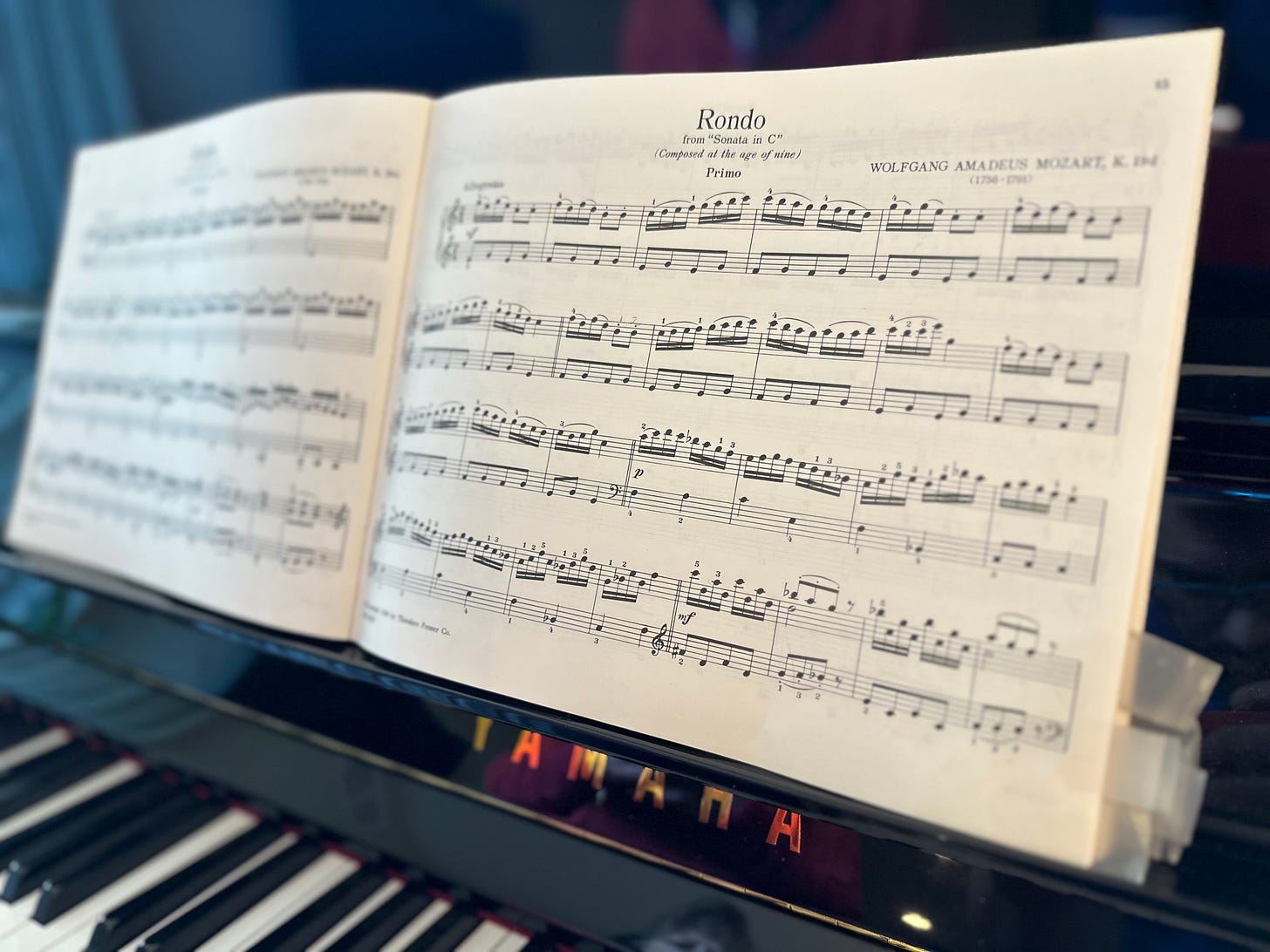

The above words are the title lines for a four-hand piano piece that Sally S and I like to play together. It’s quite simple, and between the two of us we hit almost all the right keys almost all of the time. We can even play it allegretto as it is supposed to be played. But still, it’s a bit of a challenge.

What keeps us going is looking at that subhead: “Composed at the age of nine.”

If a kid in Salzburg — Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart — could write this rondo at nine — never mind that he was already identified as a genius — well, then, we can play it.

“Let’s do the rondo,” I say to Sally after we’ve barely made our way through the five sharps of Brahms’s Hungarian Dance Number 5 and Robert Volkmann’s The Russians Are Coming.

We love the rondo for its simplicity, even though it isn’t too many measures into the piece that the composer has the player doing the primo (the one seated on the right side of the piano bench) put her left hand over the right hand of the player doing the secondo part (the one seated on the left side of the piano bench).

The way little Mozart wrote the piece, the primo person (in this case, me) putting her left hand over the other player’s right hand has to be careful and it doesn’t feel exactly natural, and every time I follow the notes and see that my left hand, in order to reach the “f” below middle C, even though there are no flats or sharps in this easy rondo, feels a bit awkward and that I could easily mess up my partner’s simple run of treble clef eighth notes if I am not careful.

When my left hand is doing its awkward thing, I imagine the insanely inspired child who wrote the piece sitting there in his house in Salzburg, grinning to himself and I imagine him getting quite a kick out of writing something that he knew would slightly confound his elders when they tried to play it, no matter how seemingly elementary it was.

I love playing the piece because even though it is now two hundred and fifty-nine years later, I can still sit on the piano bench and imagine the laughter of the young boy Mozart, who had to have had a fairly highly developed sense of humor to have been traveling all over Europe with his father entertaining royalty when other children his age were playing with blocks in European kindergartens.

Mozart’s eventual compositions — piano concertos and serenades and operas and masses and symphonies and chamber music, a seemingly endless flow of truly extraordinary works, eventually totaled, unbelievably, more than 800 pieces. It’s difficult to imagine the inspired labors that led to so much achievement in a life that ended at thirty-five years of age.

But while pondering Mozart’s unbelievable work, and what his life must have been like in the Europe of the 1700s, I do most especially love thinking about the satisfied mischievousness that a nine-year-old boy just has to have enjoyed when he penned his rondo in his Sonata in C, and imagined the arm crossings that were going to confound slightly uncoordinated four-hand piano players for centuries to come.

Did he know we would smile when we remembered him?

I think this is brilliant. Mozart would love this. (I did too)

One of your best!!!